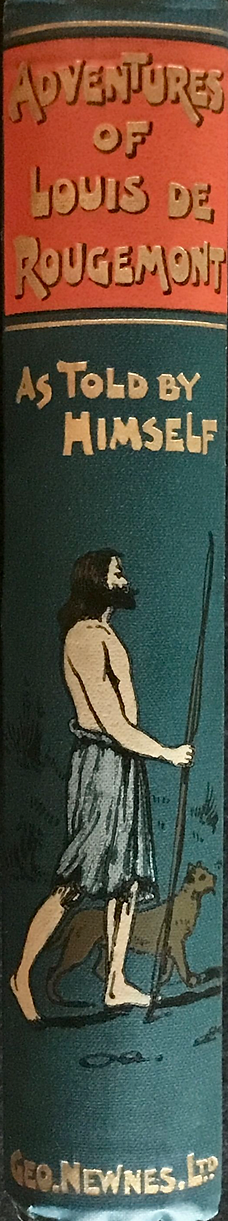

Portrait of the fabulist

Artist: Robert J Howard

TRUTH STRANGER THAN FICTION

Louis De Rougemont is one of the most fascinating yet little-known characters in post-European Australian history. After he stormed the London headlines in the northern summer of 1898, Henry Lawson declared De Rougemont had made ‘a bigger splash in three months than any other Australian writer had begun to make in a hundred years’.

Lawson predicted Louis’s book, The Adventures of Louis De Rougemont – As Told By Himself (published in England, Europe, Australia and the United States the following year) was destined to become an Australian classic: ‘one of the gospels of childhood’. But it was not to be.

I happened upon Lawson’s unpublished paean to this shadowy character by chance in an archive copy of the journal of the State Library of Victoria, while researching a work on the follies of early private European expeditions to inland Australia. I had already had several accidental encounters with Louis through old newspaper clippings and had subsequently browsed the public domain version of

his book at the Project Gutenberg website.

The story of a French merchant’s son marooned with Australian Aboriginals for thirty years seemed entirely surreal, yet it echoed accounts by other castaways and lost adventurers over the ages. De Rougemont’s sudden rise to celebrity in an era of technological wonderment, when new forms of communication were shrinking the globe and revolutionising media,

It also seemed to have strange resonances with our own time. But who was Louis De Rougemont? Castaway or crank? My curiosity was piqued and my original purpose fell by the wayside as I became set on pursuing every lead that might help reveal the truth of this unusual man’s life.

As is often the case with historical figures from nineteenth-century Australia, the real starting point was not Australia but England. In London, my quest led me to British Library Newspapers in Colindale, the UK’s national archive of British and overseas newspapers, where I found thick reams of newsprint chronicling Louis’s extraordinary journey to fame.

While De Rougemont’s original London digs near the British Museum in Bloomsbury Street had by now been radically transformed into a Radisson hotel, the Museum Reading Room, where De Rougemont had carried out his own research, is preserved much as it had been in his day, providing close insight into Louis’s experience.

Contemporary newspaper accounts were equally abundant in Australia and the United States. On my return to Australia I traced Louis’s descendants, hoping to gain access to diaries or letters written in the protagonist’s own hand. Their assistance was freely offered but there was little to tell – when De Rougemont had deserted his young family in Australia he had been deemed the blackest of sheep, and his personal papers were destroyed soon after.

Other frustrations arose – enquiries at the Royal Geographical Society in London revealed that seven letters exchanged between De Rougemont’s original magazine publisher and the Society regarding the authentication of his experiences had disappeared over the ensuing century. The Society’s endorsement of De Rougemont had later become the focus of much controversy, but I resisted the

temptation to indulge conspiracy theories.

Other explorations were more fruitful. At the height of his fame, De Rougemont was a prolific writer to popular newspapers and journals and these provide a unique record of the Fabulist’s own inimitable voice. Many of his public speeches were reported verbatim at the time. Ever the publicist, De Rougemont was also in the habit of freely distributing signed copies of his book, some of which contained

brief, often cryptic, letters to the recipient. One now in my possession

contains a note to his landlady communicating his imminent departure

for Southampton ‘due to an error’. Another promises a minister in

British Guiana that ‘all shall be revealed soon’.

Celebrity attracts company like moths to light and many of De Rougemont’s contemporaries also wrote detailed accounts of their encounters with the man in

books, letters and journals. These proved to be invaluable sources. However, only two previous books deal with De Rougemont’s life in any real detail – a twenty-three page pamphlet entitled The Greatest Liar on Earth by Australian journalist Frank Clune, published in 1945, and The Most Amazing Story A Man Ever Did Live To Tell, a more substantial account written by Geoffrey Maslen in 1977.

Most elusive of all the leads I followed, but eventually one of the most satisfying, was the true story of Louis De Rougemont’s fateful encounters with Charles Milward, a New Zealand Shipping Company captain who was a distant relative to the late, celebrated and much travelled author Bruce Chatwin.

Chatwin had written of De Rougemont’s meetings with Milward in his first book In Patagonia, but controversy has since surrounded the authenticity of his accounts. In the course of his travels, Chatwin had visited Charles Milward’s daughter in Lima, Monica Milward Barnett, who permitted him to peruse the captain’s journals.

Without Barnett’s knowledge, however, Chatwin went on to reproduce large sections of it in In Patagonia. A copyright wrangle ensued. Though Chatwin and Barnett later resolved their dispute and became friends, the journals had not been sighted since. As this book fast approached the printer’s press, I finally traced Charles Milward’s grandson, Christopher J. Barnett.

Despite his mother’s experience with Chatwin, Christopher very kindly offered his assistance and after a few days’ search rediscovered the transcript of Milward’s journal in an unmarked box in his basement. The accounts of Louis De Rougemont’s encounters with Charles Milward in this book are directly based on these journal entries (Milward’s original material remains copyright Monica Milward Barnett).

Bruce Chatwin’s biographer Nicholas Shakespeare said of his inventive subject that he told not ‘a half-truth but a truth and a half ’. It is a description that could be equally applied to Louis De Rougemont. The Fabulist is an exploration of the life and times of a man whose talents for self-invention were unparalleled. Inevitably, the nature of such a life means that a complete documentary record is hard

to establish.

Some of De Rougemont’s own tales were further embellished by acquaintances and reporters. Official records are no more dependable – even Louis De Rougemont’s death certificate reveals posthumous amendments to his age and occupation. All newspaper, book and journal extracts reproduced in The Fabulist are faithfully rendered, but on occasion I have been faced with wildly conflicting accounts of events. In a few cases, some licence has been taken in recreating conversations and events based on all available fact.

My intention has been to strip back the thin veneer between fact and fiction and paint a detailed portrait reflecting the many dimensions of this remarkable - and often inscrutable - man.

Rod Howard